Osteopaths understand that everything in the body is connected. This even goes beyond muscles, joints,…

Meniscus Tears

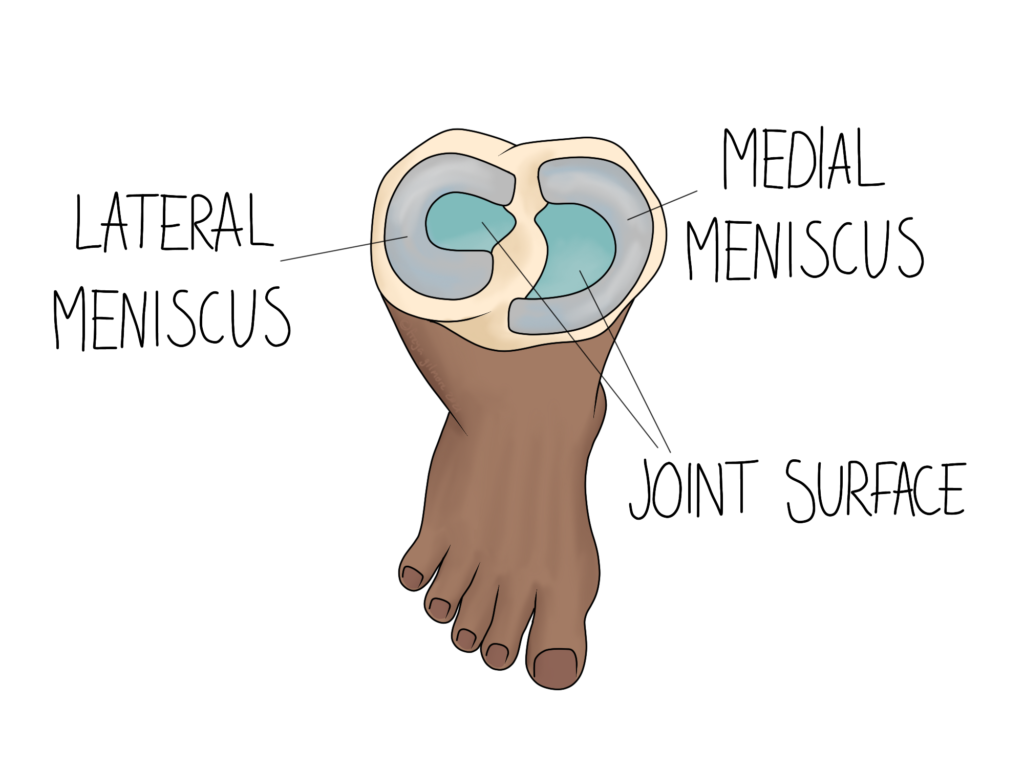

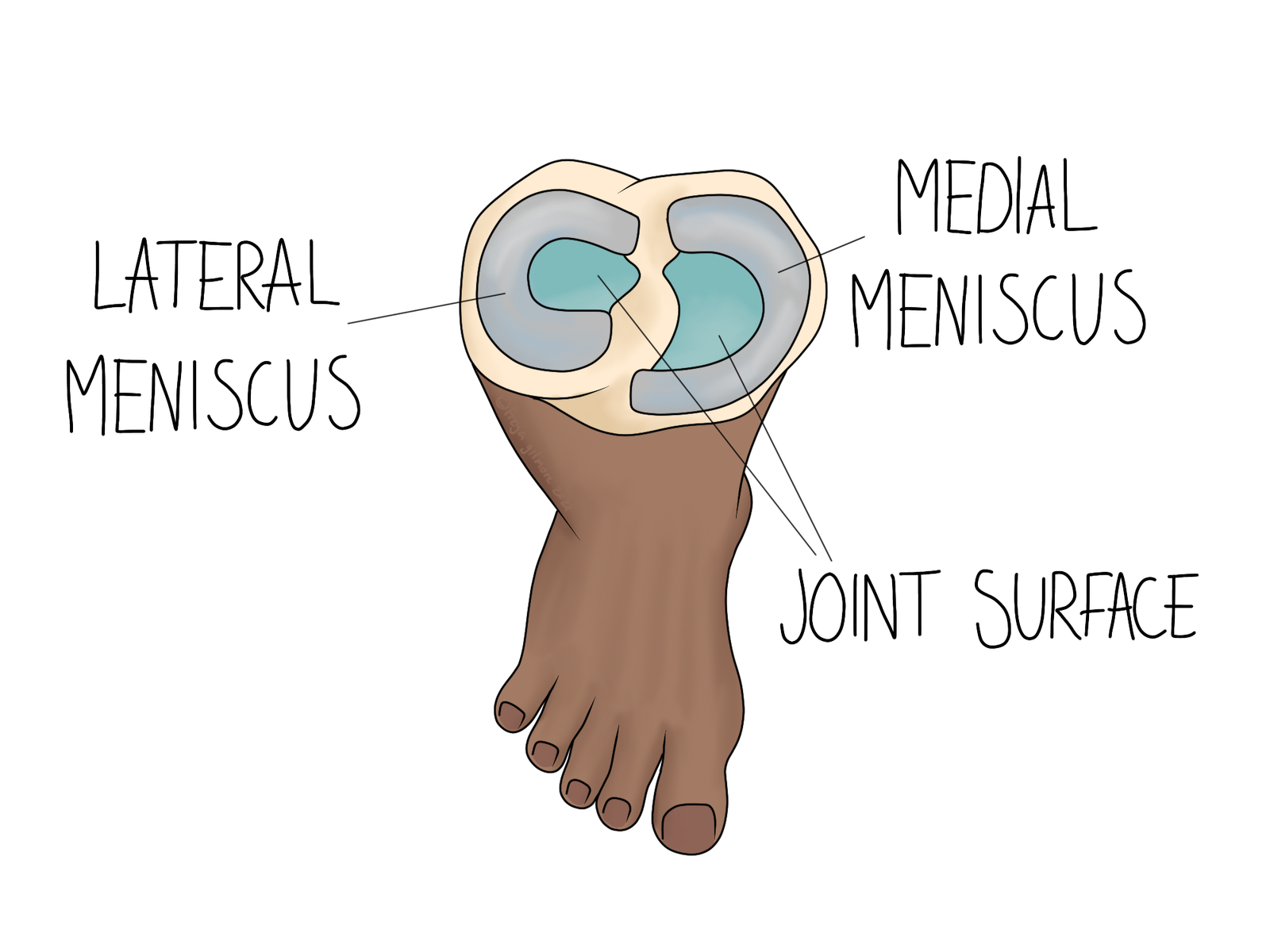

The menisci (singular: meniscus) are two C-shaped pieces of cartilage in each knee. Their roles are to help stabilise and cushion the knee, as well as to provide some shock absorption.

Signs and Symptoms of Meniscus Tears

The onset of a meniscus injury is often traumatic, although the pain levels at the time are variable. Symptoms can also fluctuate after the initial onset, while the injury is still present. Sometimes this is due to the shape of the injury, although this can only be identified with imaging and is usually not clinically relevant unless surgical repair is indicated.

Pain is usually isolated to deep within the knee, and may be described as a constant ache with a sharp “catching” pain on some movements. There may also be locking and stiffness or restriction of movement. Swelling can also come and go from onset to resolution.

Common Shapes of Meniscus Tears

- bucket handle tear

- flap tear

- radial tear

Both the bucket handle and flap tears are shapes in which some of the meniscus can move in and out of the correct position. In these cases, symptoms may seem to resolve, only to return with a vengeance when repositioned by an otherwise innocuous movement.

Mechanism of Injury

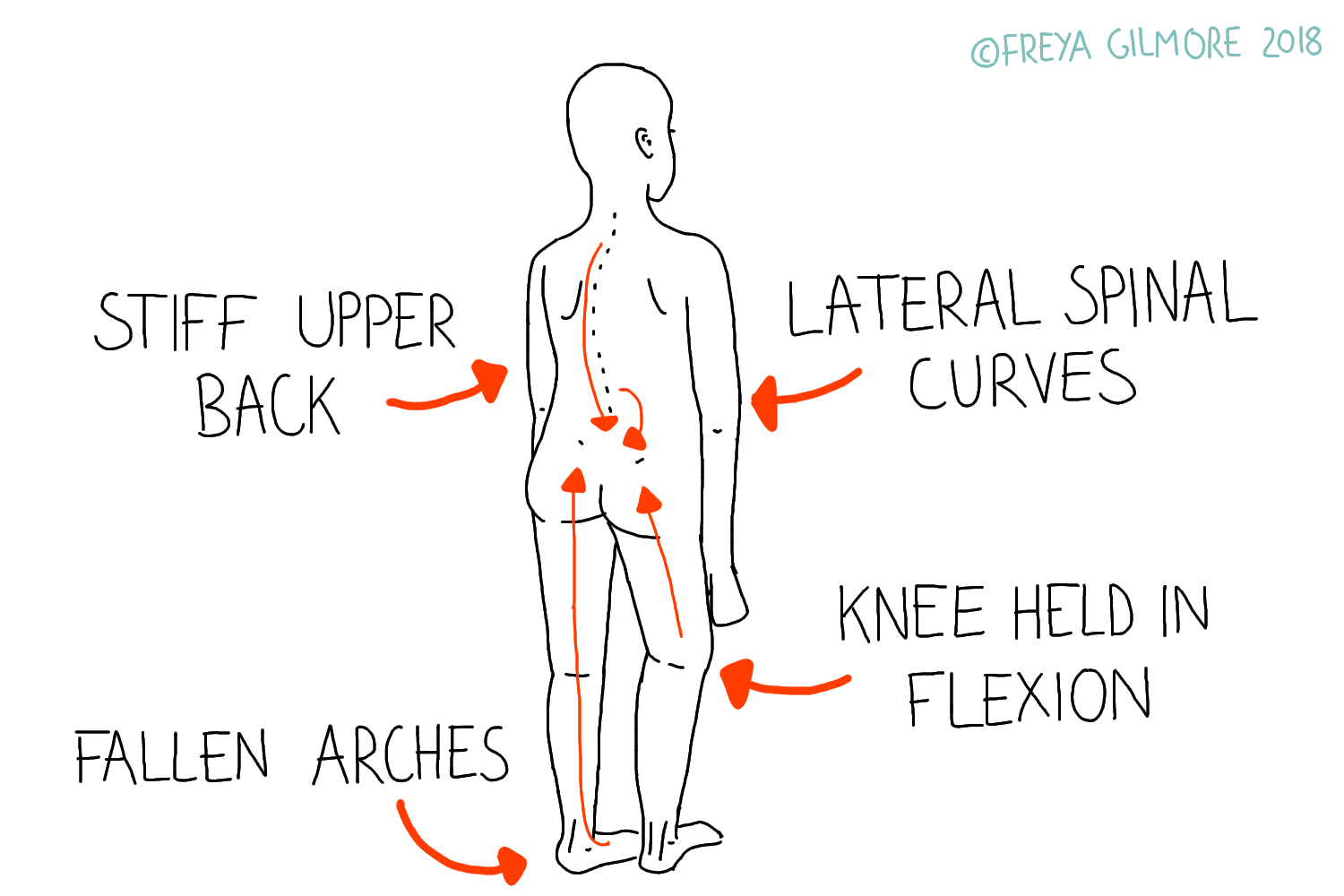

The movement that menisci really don’t like is twisting through the knee, especially while weight-bearing. The leg that is planted while kicking a football can be susceptible to injury in this way. As we age, the cartilage begins to degenerate, and even simple movements can eventually be enough to cause a tear.

Degenerative tears are most likely to affect men over the age of 60. Those who are particularly at risk might climb a lot of stairs or squat or kneel as part of their daily demands.

Managing Meniscus Tears

The menisci are made of cartilage, so they have a relatively poor blood supply. Instead, they rely on diffusion to absorb nutrients and dispose of waste. As a result, healing is often a slow process, but your osteopath can support you in this. Osteoarthritis is another example of a cartilage problem, and sometimes a similar management approach is suitable. In both cases, we prioritise improving fluid health. This means encouraging the fluid within the joint to refresh frequently. The reason for this is that when joint fluid has been in situ for a while, it will have exhausted its nutrients and taken on a lot of waste. If the waste levels are high enough, diffusion dictates that the cartilage will no longer be able to offload its waste. It will also receive no new nutrients, as there are none there to take. Techniques and exercises to drain any swelling can help to encourage old fluid on its way, making space for new fluid. Ensure you stay well hydrated too.

Beyond fluid health, encouraging full movement within the joint is key. Diffusion of nutrients and fluids is good, but compression and decompression is better. Continuing to move the knee through the fullest range possible allows the cartilage to act like a sponge. Pressure squeezes out the waste, and its absence enables the uptake of nutrients.

Progress is usually relatively slow, but for more complex cases, we may refer you back to your GP for further investigation.